Greenwood Rising - Story of a Massacre

- Jan 20, 2022

- 5 min read

Updated: Apr 29, 2022

The thing that struck me, that grabbed my attention, dropped my jaw and provided a glimpse of the devastation that occurred a century ago, came soon after entering the doors of Greenwood Rising in Tulsa, Oklahoma

It wasn’t some elaborate display with lights and eight-feet-tall images. It was a small, maybe 4 x 8-inch, backlit photo on the wall opposite of the reception desk.

It shows Black Wall Street before that devastating night 100 years ago when the community was burned to the ground and somewhere between 75 and 300 people were massacred. No one has ever been able to put an exact count on the number. Still today they are debating about the possibility of mass graves within Tulsa’s city limits.

I don’t know what I was thinking before I entered Greenwood Rising. Obviously I wasn’t thinking. The image in my brain of what a business district looked like in 1921 wasn’t nearly this modern.

I suppose I was imagining some combination of wooden and brick structures. I mean, even during my youth in the 1960s it was common to see neighborhood stores made from wood.

But that was not this. This photo depicted a bustling community, packed with brick structures, men in suits, cars lining the paved street and a bus driving down the middle. If the cars were modern and the photo in color, it wouldn’t look much different than many communities today.

And, in a single night, it was all gone.

If you don’t know the story by now, you should. Let me add, there’s no shame in not knowing the story. It wasn’t told. Even those who survived it did not speak of it.

I have a degree in history and it was never once discussed in my classes. I just began to hear about it a year ago as it approached the 100th anniversary and Greenwood Rising was preparing to open its doors on August 4, 2021.

A century ago, Tulsa’s Greenwood area was an entirely Black neighborhood on the edge of the city. The early 1900s were a time of high segregation throughout our country. Roughly 10,000 Blacks lived in Tulsa at the time, most of them in the Greenwood neighborhood. All of them were essentially required to do their shopping in Greenwood away from the white stores in the rest of Tulsa.

In an ironic twist, that requirement became a benefit to Greenwood.

With all of Tulsa’s Blacks shopping in the neighborhood, it was extremely prosperous. There were a dozen or more millionaires living there in what became known as Black Wall Street.

As with countless other cities at the time, there were ongoing tensions. It’s been reported more than 3,000 of Tulsa’s residents were members of the Ku Klux Klan.

On May 30, 1921, a Black teenager named Dick Rowland stepped into the elevator at an office building in Tulsa. At this point in time, elevator operators controlled the buttons taking passengers to their chosen floor.

After Rowland entered the elevator, the operator, a young white female named Sarah Page, screamed. Rowland ran off and was arrested the next morning.

There’s a wide number of stories about what happened in that elevator and what later happened to Rowland. Some say the elevator was known to not stop properly at each floor and Rowland simply tripped when stepping on.

Others say Page knew Rowland and they may have even been romantically involved. The Tulsa Tribune newspaper reported he attacked her and tore her clothes, but the newspaper was also well known for stirring racial tensions in in its articles.

Most agree Rowland escaped Tulsa immediately after the massacre with many believing the Tulsa sheriff secretly helped him in order to avoid a riot at the jail. We do know the case against Rowland was dismissed four months later after Page sent a letter to the County Attorney stating she did not wish to prosecute.

The Tulsa Tribune story came out the same day Rowland was arrested and that night, May 31, the rioting began. It lasted 16 hours with white mobs starting fires, firing shots and even reports of fire bombs being thrown from airplanes above.

In the end, 35 city blocks were burned to the grown and more than 1,200 homes were destroyed. In addition to the deaths, there were at least 800 injuries. More than 8,000 were left homeless.

There are many online resources available to learn more about the massacre. The History Channel offers a fairly concise one.

None of them tell it as well as Greenwood Rising. It pulls no punches.

The museum walks visitors chronologically through Greenwood’s birth as a neighborhood, its prosperous times, the tragedy of May 31 and what has happened since.

One of the more cool things near the beginning is a barber shop where visitors sit in the barber chair and eavesdrop on the conversation of the three barbers plying their trade. As you sit in the chairs, videos of the barbers are projected onto the mirrors in front of you, magically giving you the feeling the barber is actually working on your hair.

Their conversation is what you might expect in a barber shop, the topics of the day and what is happening in the community, artfully providing you with a feel for what life was like, before the riot.

From there though, things quickly turn dark. Before entering the next rooms, attendees are notified of their graphic nature and a side hallway allows people to bypass the rooms.

Inside you see newspaper images from the time, KKK artifacts, chains used to bind slaves, and whips and other devices used to torture them.

Next to that is a room with three tall screens, made to look like they were walls left from buildings that had crumbled. The audio and video reflect the tragic scenes of May 31.

People are screaming, not understanding what was happening, calling out to their family. Bullets whistle, planes flying overhead dropping their firebombs and it is easy to imagine the growing flames that succumbed the buildings.

Greenwood did rebuild and became a viable neighborhood once again.

Sadly, it did not last. Under the banner of urban renewal, an interstate highway was built through the community in the 1960s, cutting it in half. Now there are only a handful or so of businesses along a maybe two block stretch, beginning immediately across the street from the Greenwood Rising Museum.

You can learn more about that on the Smithsonian Magazine’s website.

Your final stop at Greenwood Rising asks what your contribution will be to preventing such a tragedy from ever happening again. You’re provided an iPad on which to type out your answer, which is then added to the many others projected about the walls.

Mine is to share this story with you.

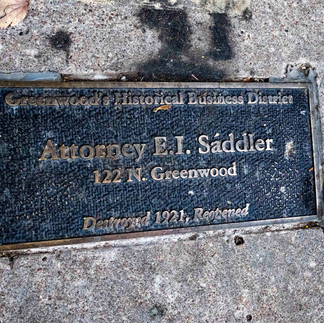

Note: If you do visit Greenwood Rising, take the time to also walk down what is left of Black Wall Street. Embedded in the sidewalk are plaques listing the businesses that once thrived there, hotels, cafes, print shops, attorneys and more.

If you continue your drive down the street, underneath the highway bridge that now cuts through it, you’ll find the Vernon AME Church. People hid in the church basement during the massacre and the only surviving foundation from that time sits under the church.

Finally: The Greenwood Massacre is not alone in our nation’s history. 200 Black farmers and their families were killed in Elaine, Arkansas, in 1919. Anywhere from six to 60 Blacks were killed in Ocoee, Florida, in 1920 when they attempted to vote in the Presidential election. The list goes on.

Here are a couple of resources if you’d like to learn more:

Tulsa isn’t the only race massacre you were never taught in school – Washington Post

Massacres in U.S. History – Zinn Education Project

-------------------------------------------------

**I allow use of my photos through Creative Commons License. I'm not looking to make money off this thing. I only ask you provide me with credit for the photo by noting my blog address, alansheaven.com, or a link back to this page.

Comments